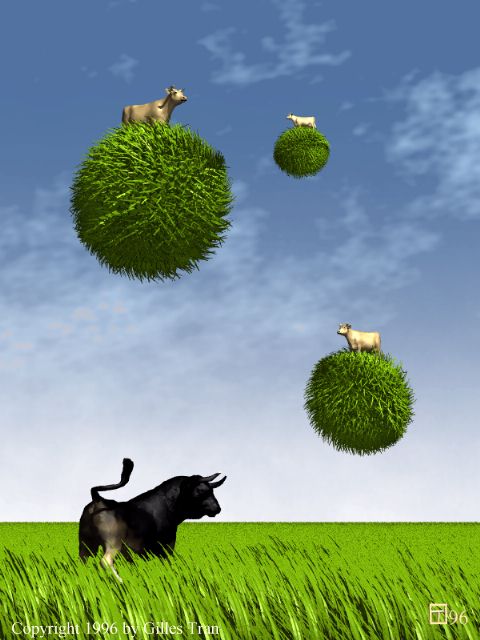

Nobody knew how it had begun. It was told that in Portugal, a man named Alavaro Da Costa had found one of them stuck to the ceiling, like a spider. But Alvaro Da Costa was untraceable. The Portuguese were hardly to blame, though, because the epidemic centres were spread all over Europe, with a predilection for the border areas. Switzerland was particularly affected. When autumn came, mooing and tinkling flocks took off, got on an updraft and passed over the Alps. They drifted along the high winds until they landed in the Camargue delta, where the small black bulls greeted the fair sex with enthusiasm. They rested there until the cold set in. Then they left, light-uddered, to Africa.

Crossing the Mediterranean was fatal to many first-timers, whose navigational skills were just awakening. Planes used to be a hazard, but the airlines had quickly learned to avoid their migratory paths. Now, the main danger came from the other herds. One flock, hidden by a cloud, would suddenly collide with another, and wounded animals from both parties would fall from the sky, howling, down to the sea, sometimes right on a cargo liner full of human passengers terrified by these kamikazes of a new kind. Once the African coast was in sight, the survivors quickly gained altitude and flew at high speed over Lybia, Chad and Sudan to avoid the flak. Then there was a slow glide towards Kenya and its national parks, where the gnus would keep them company during the winter months. This migratory ritual had its exceptions, though. Some mavericks always flew in the opposite direction, and the Russians had reported frozen cemeteries of